Race Conditions in Hotel Booking Systems: Why Your Technology Choice Matters More Than You Think

Published on: 1st Feb, 2026 by Amitav Roy

While reviewing developer forums last month, one particular post-mortem stood out for its sheer gravity. A booking platform had double-booked their premium suites during New Year's Eve. Two customers received confirmation emails within seconds of each other. Both had valid booking IDs. Both had been charged. But both were for the same room.

The thread detailed the aftermath - angry customers arriving at the front desk during check-in, emergency refunds being processed, frantic calls between the support and hotel management. But what caught my attention wasn't the incident itself. It was buried in the comments: another developer mentioned they'd had the exact same problem, but their fix was completely different because they were using a different tech stack.

That got me thinking. I started collecting these stories - case studies from production systems that hit concurrency problems under load. What I discovered was fascinating: the same logical problem (preventing double bookings) had radically different solutions depending on the underlying technology.

Why This Matters (And Why I'm Writing This)

After reading dozens of these post-mortems and case studies, a pattern emerged. Concurrency bugs are nearly impossible to catch in development. You can't reproduce them reliably. Local environments with one user clicking buttons don't expose the problem. Even staging environments with modest traffic won't trigger race conditions consistently.

Then production happens. Traffic spikes during a holiday. Hundreds of users simultaneously try to book the last available room for New Year's Eve. Systems that worked perfectly for months reveal fundamental flaws.

The cost isn't just technical - it's reputation, customer trust, and revenue. Every case study I read emphasized this: a double booking during peak season means turning away paying customers, issuing refunds, and dealing with angry reviews. In hospitality, where margins are thin and reputation is everything, these failures are expensive.

But what fascinated me most across these case studies was this: the complexity of solving this problem varied dramatically based on the technology stack. What one team thought was a universal concurrency challenge turned out to be fundamentally different depending on whether they were using PHP, Node.js, or Python with asyncio.

This realization sent me down a deep research path - not just understanding how to fix race conditions, but why different technologies make the problem easier or harder to solve in the first place.

The Core Problem: What We're Actually Fighting Against

Every hotel booking system, regardless of technology, must protect against three fundamental concurrency issues. Let me walk you through each one with the kind of detail I wish someone had explained to me.

Race Conditions: When Timing Determines Truth

Imagine two users, let's call them Alice and Bob, both trying to book the last available room. Here's what happens in a system without proper protection:

- Alice's request hits your server: "Show me available rooms"

- Bob's request hits your server: "Show me available rooms"

- Both queries check the database: "SELECT available FROM rooms WHERE room_id = 101"

- Both see: available = 1

- Alice's request: "Great, I'll book it" → UPDATE rooms SET available = 0

- Bob's request: "Great, I'll book it" → UPDATE rooms SET available = 0

Both bookings succeed. You've just double-booked your last room.

The insidious part? This happens in microseconds. Your application logs might not even show the overlap. The database processed both transactions. Everything "worked" according to the code. But the outcome violates your business logic: one room, two bookings.

Lost Updates: When One Change Overwrites Another

This one's subtler. Imagine your system allows updating room prices and availability simultaneously. The night manager adjusts the price while the booking system updates availability. Without proper isolation:

- Transaction A reads: room price = $200, available = 5

- Transaction B reads: room price = $200, available = 5

- Transaction A updates price to $250 (available stays 5)

- Transaction B updates available to 4 (price stays $200)

One of those updates gets lost. Either you're selling a $250 room for $200, or your availability count is wrong. Both are problems, just in different ways.

Dirty Reads: When You Act on Incomplete Information

Your booking system reads the room count while another transaction is updating it. You see the intermediate state—maybe available = 0 when it's actually being set to 5 as a block of rooms gets released. You tell customers "sold out" when rooms are actually available.

These aren't theoretical problems. They happen in production, and when they do, they're difficult to debug because the race condition might only occur under specific load patterns.

How Technology Choice Affects Complexity (The Part That Surprised Me)

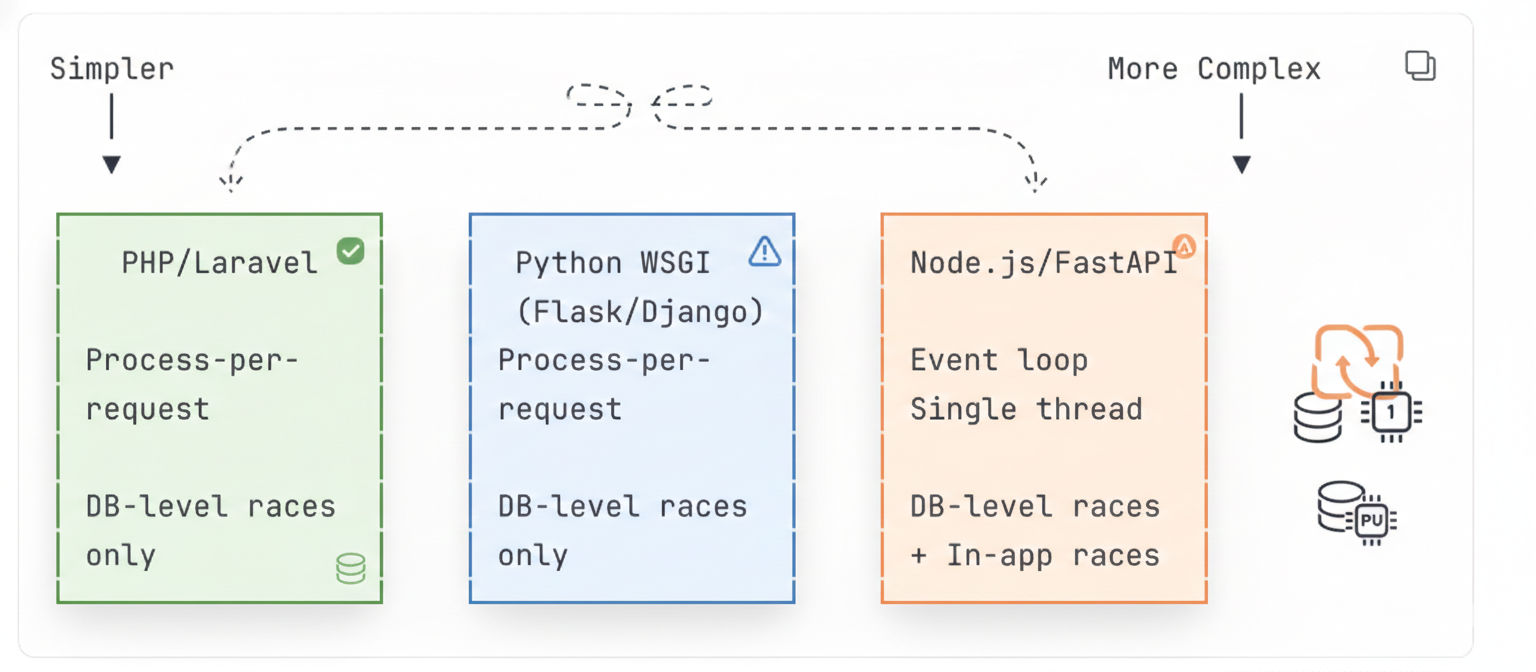

After reading through these case studies, I started to see patterns in how different teams approached the same problem. What I discovered completely reframed how I think about technology choices for transactional systems.

The fundamental insight: concurrency protection exists at two distinct layers—the application layer and the database layer. Different technologies require you to think about one layer, or both.

Here's the spectrum I mapped out from the case studies:

PHP and Traditional Python: The Gift of Simplicity

PHP and Traditional Python: The Gift of Simplicity

PHP with Apache or Nginx, and Python running under Gunicorn or uWSGI, share a beautiful characteristic: process-per-request architecture. Each incoming HTTP request gets its own isolated process. That process handles the request from start to finish without interruption.

What this means in practice: your application code runs synchronously. When you write:

$inventory = RoomInventory::where('room_id', $roomId)->first();

if ($inventory->available > 0) {

$inventory->decrement('available');

Booking::create([...]);

}

No other request can interleave with this code at the application level. Your code executes from line 1 to line 3 without interruption. The only place race conditions can occur is at the database layer, where multiple PHP processes might query the database simultaneously.

This is huge. It means you only need to think about one layer of protection—the database. Your application code doesn't need locks, mutexes, or synchronization primitives. The architecture handles that for you.

Node.js and FastAPI: The Async Complication

Node.js and Python's asyncio (used by FastAPI) introduce a different model: a single-threaded event loop with async/await. This is fantastic for I/O-bound applications—one server can handle thousands of concurrent connections efficiently.

But there's a catch. Every time your code hits an await keyword, your function can be suspended, and another coroutine can start executing. Your code interleaves at every async boundary:

async function bookRoom(roomId, date) {

const inventory = await db.query(

'SELECT available FROM rooms WHERE room_id = ?', [roomId]

);

// ⚠️ Between these two awaits, another request might execute

if (inventory.available > 0) {

await db.query(

'UPDATE rooms SET available = available - 1 WHERE ...'

);

await db.query('INSERT INTO bookings ...');

}

}

Between the SELECT and the UPDATE, another booking request might execute its SELECT, see the same available count, and proceed with its own UPDATE. You've got a race condition at the application layer, not just the database layer.

This means you need protection at two levels: database transactions to handle multiple server instances, and application-level locks or atomic operations to handle the async interleaving within a single process.

What Actually Works: Practical Solutions by Technology

After researching these patterns across different case studies, I started to see what actually works in production. Here are the practical solutions, starting with the simplest approaches.

The PHP/Laravel Way: Database-Level Protection Only

In Laravel, two approaches work well, each suited to different scenarios.

Approach 1: Atomic Updates for Simple Operations

This is the recommended default for straightforward increment/decrement operations:

DB::transaction(function () use ($roomId, $date) {

$updated = RoomInventory::where('room_id', $roomId)

->where('date', $date)

->where('available', '>', 0) // Condition in the UPDATE itself

->decrement('available');

if ($updated === 0) {

throw new RoomUnavailableException();

}

Booking::create([...]);

});

The database executes this as a single atomic operation:

UPDATE room_inventory

SET available = available - 1

WHERE room_id = ? AND date = ? AND available > 0

If two requests hit simultaneously, the database serializes them internally. The first succeeds (available goes from 1 to 0). The second finds no matching row (the WHERE available > 0 condition fails) and returns 0 rows affected.

This is elegant because there's no explicit locking. The database handles serialization. Performance under load is excellent because you're not holding locks—you're just executing a single UPDATE statement.

Approach 2: Pessimistic Locking for Complex Logic

When you need to read, compute, and write based on multiple conditions, SELECT FOR UPDATE is the right tool:

DB::transaction(function () use ($roomId, $date) {

$inventory = RoomInventory::where('room_id', $roomId)

->where('date', $date)

->lockForUpdate() // Locks this row

->first();

if ($inventory->available > 0) {

// Complex business logic here

$price = $this->calculateDynamicPrice($inventory, $date);

$inventory->decrement('available');

Booking::create([

'room_id' => $roomId,

'date' => $date,

'price' => $price,

]);

} else {

throw new RoomUnavailableException();

}

});

lockForUpdate() places an exclusive lock on the row. Other transactions trying to read that row with FOR UPDATE will block and wait until the first transaction commits or rolls back.

The trade-off: this can cause contention under high load. If hundreds of users are trying to book the same room, they queue up waiting for the lock. But it guarantees you're working with data no one else can modify.

The FastAPI/Node.js Way: Two-Layer Protection

With async runtimes, you need to think about both database and application-level protection.

Database Layer (Same Concepts, Different Syntax)

The atomic update approach in FastAPI with SQLAlchemy:

from sqlalchemy import update

async def book_room_atomic(

session: AsyncSession,

room_id: int,

date: date

):

async with session.begin():

result = await session.execute(

update(RoomInventory)

.where(RoomInventory.room_id == room_id)

.where(RoomInventory.date == date)

.where(RoomInventory.available > 0)

.values(available=RoomInventory.available - 1)

)

if result.rowcount == 0:

raise RoomUnavailableError()

session.add(Booking(...))

The pessimistic locking approach:

async def book_room_pessimistic(

session: AsyncSession,

room_id: int,

date: date

):

async with session.begin():

result = await session.execute(

select(RoomInventory)

.where(RoomInventory.room_id == room_id)

.where(RoomInventory.date == date)

.with_for_update() # SELECT FOR UPDATE

)

inventory = result.scalar_one()

if inventory.available <= 0:

raise RoomUnavailableError()

inventory.available -= 1

session.add(Booking(...))

Application Layer (The Critical Addition)

For any shared state in memory—caches, rate limiters, counters—you need locks to prevent race conditions at async boundaries.

FastAPI (Python) Example:

import asyncio

class BookingService:

def __init__(self):

# Per-room locks to avoid blocking unrelated bookings

self._locks: dict[str, asyncio.Lock] = {}

def _get_lock(self, room_id: int, date: date) -> asyncio.Lock:

key = f"{room_id}:{date}"

if key not in self._locks:

self._locks[key] = asyncio.Lock()

return self._locks[key]

async def book_room(self, room_id: int, date: date):

async with self._get_lock(room_id, date):

# Only one coroutine can execute this block

# for this specific room/date combination

await self._do_booking(room_id, date)

Node.js Example:

// Using the async-mutex package: npm install async-mutex

import { Mutex } from 'async-mutex';

class BookingService {

constructor() {

// Per-room locks to avoid blocking unrelated bookings

this.locks = new Map();

}

getLock(roomId, date) {

const key = `${roomId}:${date}`;

if (!this.locks.has(key)) {

this.locks.set(key, new Mutex());

}

return this.locks.get(key);

}

async bookRoom(roomId, date) {

const mutex = this.getLock(roomId, date);

// Acquire the lock - other requests will wait here

const release = await mutex.acquire();

try {

// Only one request can execute this block

// for this specific room/date combination

await this.doBooking(roomId, date);

} finally {

// Always release the lock, even if an error occurs

release();

}

}

}

Critical caveat: These locks only protect within a single process. If you're running multiple FastAPI workers or Node.js processes (which you will in production), database-level protection is still essential. The application lock is defense-in-depth for shared state within the process.

Why PHP Doesn't Need This

In PHP, this code has no race condition:

function bookRoom($roomId, $date) {

$inventory = DB::select('SELECT available FROM rooms WHERE ...');

// No other request can interleave here

if ($inventory->available > 0) {

DB::update('UPDATE rooms SET available = available - 1 ...');

DB::insert('INSERT INTO bookings ...');

}

}

Each PHP request runs in its own process. While Request A executes line 4, Request B is in a completely separate process—they can't interleave within the application code.

The database-level race condition still exists (both processes can SELECT simultaneously), which is why you still need atomic updates or FOR UPDATE. But you don't have the additional complexity of async interleaving.

Lessons from Production: What the Case Studies Taught Me

Analyzing these production incidents revealed several patterns that textbooks don't capture.

Start with the Simplest Solution That Works

Across multiple case studies, the teams that recovered fastest were those who rebuilt their systems with atomic updates as the default. For 90% of booking operations, this was sufficient. Only when business logic became complex did they need pessimistic locking.

The atomic update pattern—embedding the condition in the UPDATE statement—eliminates the read-then-write window entirely. It's faster, simpler, and easier to reason about than explicit locks.

Technology Choice Matters More Than You Think

If I were building a new booking platform today, I'd seriously consider PHP or traditional Python (Django/Flask with Gunicorn) specifically because they limit concurrency concerns to one layer. The process-per-request model is a feature, not a limitation.

That doesn't mean Node.js or FastAPI are wrong choices—they offer real benefits for I/O-bound workloads. But you're trading simplicity in the concurrency model for efficiency in resource usage. Make that trade-off consciously, not accidentally.

Testing Concurrency is Genuinely Hard

Every case study emphasized this: you can't reliably reproduce race conditions in development. The successful teams used load testing tools that simulate hundreds of concurrent users hitting the same endpoint simultaneously. Even then, triggering the race condition requires specific timing.

The best defense: write code that's correct by construction. Use atomic operations. Avoid read-then-write patterns. Make the database handle serialization rather than trying to coordinate it yourself.

Database Protection is Non-Negotiable

Regardless of your runtime—PHP, Node.js, or FastAPI—you always need database-level protection. Multiple server instances will hit your database simultaneously. The application layer can't protect against that.

Even if you're running a single Node.js process with perfect application-level locking, the moment you scale to multiple processes or servers, those application locks become useless for database protection.

The Decision Framework I Use Now

When I evaluate technology for systems where concurrency matters, I ask these questions:

What's my team's expertise? If they're PHP developers, fighting async semantics in Node.js adds risk for marginal benefit in a transactional booking system.

What's the concurrency profile? Read-heavy with occasional writes? Write-heavy with conflicts? Pure semantic similarity searches? The answer determines whether process-per-request, async, or multi-threading makes sense.

What's my operational capacity? Can we manage the complexity of distributed locks and async debugging? Or do we need the simplicity of process isolation?

What's the cost of failure? In a booking system, double-booking during peak season is catastrophic. I'll trade some performance for simpler, more obviously correct concurrency handling.

What This Means for Your Next System

If you're building a hotel booking system—or any transactional system where correctness under concurrent load is critical—here's my advice:

Default to atomic operations. Make the database handle serialization. Embed your conditions in UPDATE statements. This works across all technologies and requires no application-level coordination.

Use pessimistic locking when business logic requires read-compute-write patterns. SELECT FOR UPDATE guarantees isolation at the cost of potential contention. Accept that trade-off when correctness demands it.

If you must use async runtimes, protect shared state explicitly. Don't assume your intuitions from synchronous code apply. Every await is a potential interleaving point.

Choose technologies that match your problem. PHP's process-per-request model is genuinely simpler for transactional systems. That simplicity has value.

Test under realistic load. Develop load testing scenarios that simulate your peak traffic. Concurrency bugs hide until you hit them in production.

The craft of building reliable systems isn't about knowing every advanced technique. It's about understanding the fundamental problems, recognizing which layer of the stack should solve each problem, and choosing technologies that make correct solutions easier rather than harder.

Reading through these production post-mortems taught me these lessons vicariously. I'm sharing them so you don't have to learn them the hard way—at 11 PM with angry customers on the phone and uncomfortable questions from your CTO.

Build systems that are correct by design. Choose simplicity when simplicity works. And remember: the best concurrency bugs are the ones your architecture makes impossible in the first place.